The question of whether AI will replace interpreters is no longer just about technological capability—it’s about what we value and desire in human communication. At the Interpreting Europe Conference, Jurgen Schmidthuber suggested that interpreters may eventually be replaced by machines. While this may be technically feasible in the future, it is essential to explore the ethical and cognitive implications beyond what is simply possible.

One key difference between humans and machines lies in the ability to self-correct. When interpreters misinterpret, they can listen to their own output and revise it—or rely on their colleagues for support. Machines, by contrast, can “hallucinate,” confidently producing false output without awareness. This brings up crucial concerns such as the opacity of ownership—who controls and accesses data when AI is used—and the opacity of liability, as it’s often unclear who is responsible when mistakes occur.

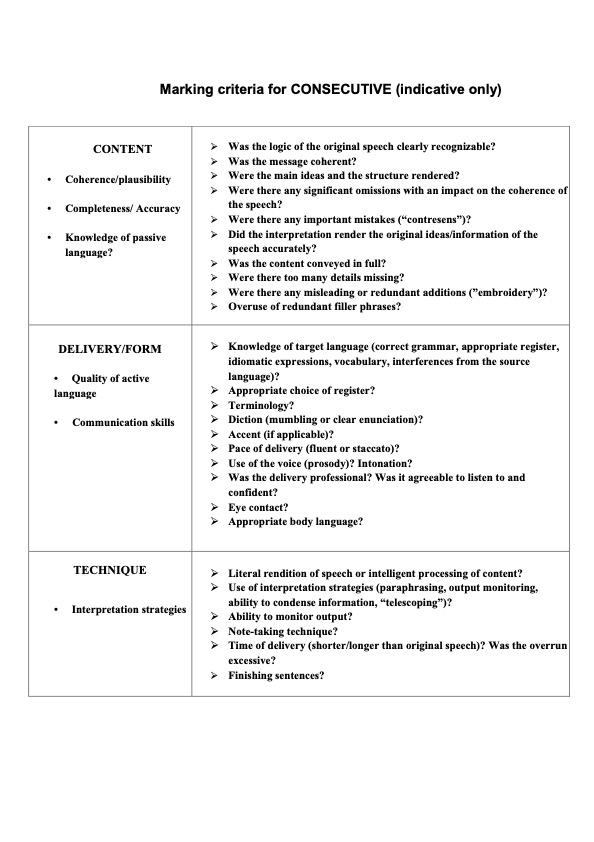

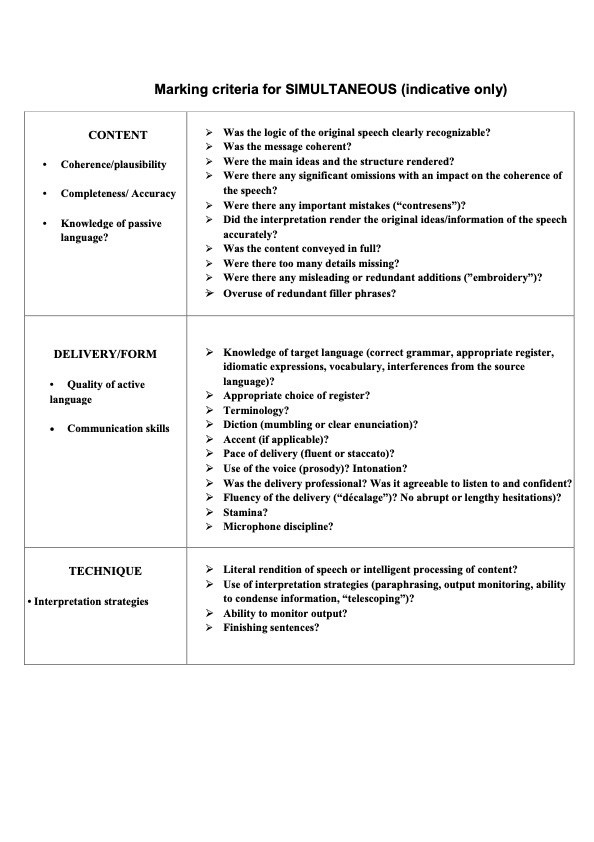

Despite the rise of AI, the EU institutions will continue to need trained human interpreters. Preparing future generations for this task involves helping them understand the complex cognitive processes involved: analysis, reformulation, shifting attention, and self-monitoring. Interestingly, as IT engineers attempt to simulate interpreting, they become more aware of its deep mental complexity.

Tools such as AI boothmates and speech-to-text software can aid students but also increase cognitive load and distract from the core task. These technologies should be used critically, not blindly. Encouraging interpreters-in-training to think deeply about how AI works can enhance their understanding and foster critical thinking. Much like the shift from analog to digital, today’s transition to AI is profound—and without thoughtful guidance, we risk depriving the next generation of insight into the very processes that define human interpretation.

Andrea GROSSO is Pedagogical Asssistance Coordinator at DG SCIC, European Commission