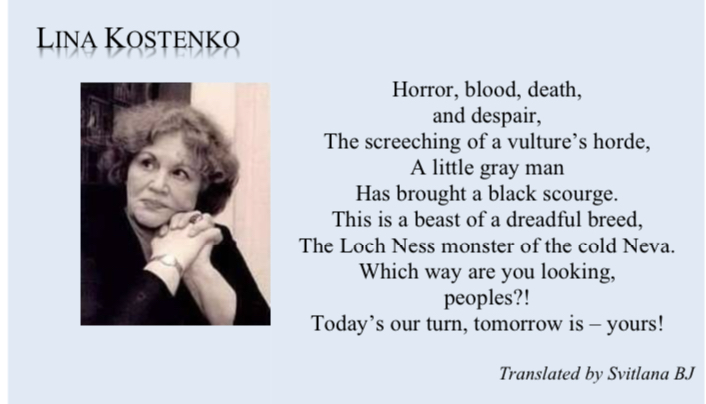

І жах, і кров, і смерть,

і відчай,

І клекіт хижої орди,

Маленький сірий чоловічок

Накоїв чорної біди.

Це звір огидної породи,

Лох-Несс холодної Неви.

Куди ж ви дивитесь,

народи?!

Сьогодні ми, в завтра – ви!

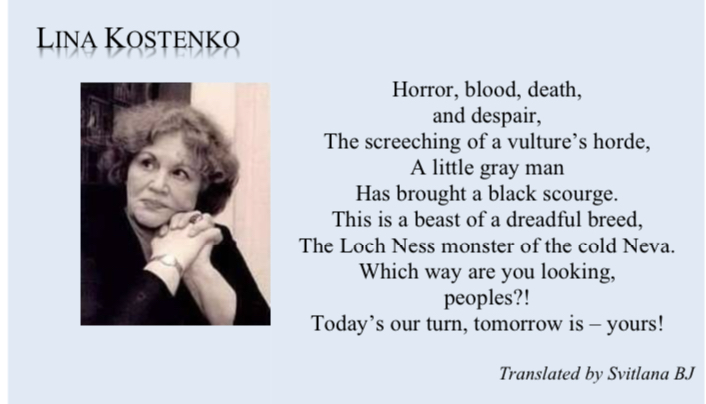

І жах, і кров, і смерть,

і відчай,

І клекіт хижої орди,

Маленький сірий чоловічок

Накоїв чорної біди.

Це звір огидної породи,

Лох-Несс холодної Неви.

Куди ж ви дивитесь,

народи?!

Сьогодні ми, в завтра – ви!

Over the years I have seen developments in interpreting come and go, and there has always been the latest threat lurking around the corner. Blend our love of being the bearers of bad tidings with the underlying insecurity of the self-employed and you have fertile ground for spreading doom and gloom.

The arrival of remote interpreting has been likened to the arrival of simultaneous many years ago, meaning that our markets and working conditions will change permanently and many of our cherished ideas are open to question.

Interpreters have always declared a professional domicile as a reference point for calculating travel costs and subsistence allowance, and usually it has been the place where the interpreter lived. This made perfect sense when we travelled to where meetings were held, but the notion of professional domicile seems immaterial in times of remote interpreting where we may work from home or from a local hub.

In the past we could explain to clients that some interpreters had to travel to the venue from elsewhere, which would involve additional cost. Now the interpreters work from their home base – they might be in their own home, working from a hub or working alongside a colleague in a hub or home set-up – but travelling has been removed from the equation. Picture a meeting that is held in Geneva or London or Mexico City with a few people in attendance. The interpreters are all working from home or a local hub, and most of the delegates are in their home base. None of the interpreters must travel, so their domicile cannot be used to establish overall fee, and even if you think it should you will be unlikely to convince your client. Once people don’t travel the reason for professional domicile disappears.

Clients can accept justified costs, but they are going to question expenses that we cannot explain. It is important to see things from the client’s angle – something we have not always been very good at – and in difficult times to meet them halfway. It is also important for us to shape what we can of the future, not dig our heels in to defend a working condition we are hard pressed to justify.

Professional domicile has not been iron-clad in the past. Colleagues would declare one place as their domicile (say Brussels) and live elsewhere (take your pick). Domicile and place of residence have not always been the same thing.

It’s important to take a broad view when looking at the changes wrought by remote interpreting. Because costs have come down clients are organising more meetings, and attendance is increasing because participants simply need to sign in – no travel is involved. In the face-to-face past a trade union meeting in Geneva would attract two or three Argentinians and a Brazilian from Latin America; now that same meeting when held remotely has 30 participants from Argentina, 40 from Brazil as well as delegates who previously were unable to travel to meetings – Colombia for example, southeast Asia, Oceania. There is now regular demand for Hindi, Bangla, Tamil, Thai, Nepali, Vietnamese and Cambodian. RSI has meant that teams can include colleagues from around the world, such as Canada, Singapore, Australia – the only limiting factor is the time zone.

People have said that remote interpreting is not what they signed up for. This may be a way to let off some emotional steam, but it seems unlikely to save existing markets because those who use our services live in the here and now. Our clients can now choose interpreters from anywhere in the world and will certainly find people who are willing to work remotely. Once a client is lost there is scant chance of their coming back.

These idle thoughts apply to the private market. The international organisations have taken the sensible decision to operate as hubs with the interpreters on site, any other solution would probably be unworkable. Clearly any departure from current arrangements would be subject to negotiation, but we might be well advised to have some ideas at the ready just in case.

None of us quite know where the current changes to the profession will take us, but I tend to be relatively upbeat about how the profession will develop because I think RSI will open new or expand existing markets providing the service offered is technically reliable. I may be wrong, but then so might anyone else willing to predict where we will be five years hence.

We need to grasp the future, not hanker after the past.

Phil SMITH, AIIC Switzerland.

Interpreting schools – beyond their best before date?

Working interpreters were already feeling the pinch when Covid-19 arrived, and they tended to think that one cause was the overproduction of newcomers by interpreting schools. People would suggest closing them, or at least putting the courses on hold for a couple of years to give the market time to right itself. Louise Jarvis is a professional conference interpreter and a trainer at the University of Bath Interpreting School and in this interview with Phil Smith she considers the role of interpreting schools and the work they do to remain relevant to current market needs. The comments and conclusions – if any – refer to interpreting into English. The situation may vary for other active languages.

Although the current crisis has hit demand for interpreters, it is important to keep our eyes on what will happen post-Covid. Demand for English booth interpreters remains high in both the UN and EU sectors: the UN is particularly keen on people with passive Russian and the EU needs new blood with German and Italian. Despite Brexit, demand for English language interpreters will hold up because of the wide use of English in all international organisations. In the language architecture of the EU, English is the load-bearing wall.

Entry testing at interpreting schools is stringent, and this is in part due to the fact that once someone has been admitted to the course it is not easy to expel them – there is a tension between academic rigour and the administrative demands of being part of a university. That same university system also makes it well-nigh impossible to put a course on hold for a year or two. Universities simply don’t work that way.

Which languages should a student choose? The UN works with six languages which do not change so the answer here is: French, Spanish and Russian – bearing in mind that the Arabic and Chinese booths are bi-directional. In the EU requirements change, but there does appear to be a looming shortage of English language interpreters working from German and Italian. Add to that the age profile of staff and freelance interpreters in the EU and there is clearly a need for new recruits. The good interpreting schools have close contacts with the international organisations so can tailor their offering to future needs.

The first thing an interpreting school impresses upon new entrants is the need to work on their mother tongue – clarity, diction, the ability to express an idea succinctly. Students also learn how to analyse a speech, what is the actual message, the structure of the speech, what are the different points and how do they relate to each other, how do you home in on the message and the intention behind the message.

Such skills are very useful in any job, so even if a student decides that interpreting is not really for them, the ability to speak in public, to analyse a speech and discern the “truth behind the words” will serve them in whatever career they choose.

Budding interpreters sometimes ask which languages they should choose, perhaps with the idea that something truly exotic will get them more work. Experience teaches that in general interpreters are best placed if they have what we might call mainstream languages (EN, FR, ES, DE, IT) and perhaps one exotic language such as Danish or Slovenian. It is also quite good if an interpreter can straddle markets, in other words appeal to both the EU and the UN.

Demand for interpreters fluctuates, language requirements change, and schools do their best to meet those demands whilst being candid to their students about future career prospects. It is something of a balancing act.

The medium and long-term prospects for the English booth remain good so interpreting schools continue to fulfil a useful and a vocational role.

And learn Italian and German. Remember, you read it here first.

Phil SMITH.